1986

While Frankie Knuckles had laid the groundwork for house at the Warehouse, it was to be another DJ from the gay scene that was really to create the environment for the house explosion – Ron Hardy. Where Knuckles’ sound was still very much based in disco, Hardy was the DJ that went for the rawest, wildest rhythm tracks he could find and he made The Music Box the inspirational temple for pretty much every DJ and producer that was to come out of the Chicago scene. He was also the DJ to whom the producers took their very latest tracks so they could test the reaction on the dance floor. {ln:Larry Heard} was one of those people.

“People would bring their tracks on tape and the DJ would play spin them in. It was part of the ritual, you’d take the tape and see the crowd reaction. I never got the chance to take my own stuff because Robert (Owens) would always get there first.” “The Music Box was underground ” remembers {ln:Adonis}. “You could go there in the middle of the winter and it’d be as hot as hell, people would be walking around with their shirts off. Ron Hardy had so much power people would be praising his name while he was playing, and I’ve got the tapes to prove it! “The difference between Frankie and Ronnie was that people weren’t making records when Frankie was playing, though all the guys who would become the next DJs were there checking him out. It was The Music Box that really inspired people. I went there one night and the next day I was in the studio making ‘No Way Back’ ” In 1985 the records were few and far between. By 1986 the trickle had turned to a flood and it seemed like everybody in Chicago was making house music. The early players were joined by a rush of new talent which included the first real vocal talents of house – Liz Torres, Keith Nunally who worked with Steve Hurley, and Robert Owens who joined up with Larry Heard to form Fingers Inc, though the duo had already worked with Harri Dennis on The It’s ‘Donnie’ -and key producers like Adonis, Mr Lee, K Alexi and a guy who was developing a deep, melodic sound that relied on big strings and pounding piano – {ln:Marshall Jefferson}.

{ln:Marshall Jefferson ‘Marshall} worked with a number of people like Harri Dennis and Vince Lawrence for projects like Jungle Wonz and Virgo, who made the stunning ‘RU Hot Enough’. But it was ‘Move Your Body’ that became THE house record of 1986, so big that both {ln:Trax – The House that built Chicago ‘Trax} and DJ International found a way to release it, and it was no idle boast when the track was subtitled ‘The House Music Anthem’, because that’s exactly what it was. Jefferson was to become the undisputed king of house, going on to make a string of brilliant records with Hercules and On The House and developing the quintessential deep house sound first with vocalist Curtis McClean and then with Ce Ce Rogers and Ten City. “I can remember clearing a floor with that record” laughs Jazzy M. “Though they’d started playing it in Manchester, most of London was still caught up in that rare groove and hip hop thing. A lot of people were saying to me ‘why are you playing this hi- NRG’ and it was hard work but people were starting to get into it.” ‘Move Your Body’ was undoubtedly the record that really kicked off house in the UK, first played repeatedly by the established pirate radio stations in London, which at the time played right across the Black music spectrum, and then by club DJs like Mike Pickering, Colin Faver, Eddie Richards, Mark Moore and Noel and Maurice Watson, the latter two playing at the first club in London to really support house – Delirium.

Radio was the key to the explosion in Chicago. Farley Jackmaster Funk had secured a spot on the adventurous WBMX station, playing after midnight every day, and it wasn’t long before he brought in the Hot Mix 5 which included Mickey Oliver, Ralphie Rosario, Mario Diaz and Julian Perez, and Steve Hurley, giving people who couldn’t go to the parties the chance to hear the music. Then there was Lil Louis, who was throwing his own parties. By this time, house was moving out of the gay scene and on to wider acceptance, though in Chicago at least it was to remain very much a Black thing. Though a number of Hispanics were on the house scene, the number of White DJs and producers could be counted on one hand.

The labels were still mostly limited to the terrible twins that were to dominate Chicago house for the next two years Trax and DJ International. Between them they had nearly all the local talent sewn up and by popular consent they were just as dodgy as each other, with rumors and stories of rip-offs and generally dubious activity endlessly circulating. Everybody it seemed, was stealing from everybody else. One that remains largely untold involved Frankie Knuckles. “This was the story at the time” recalls Adonis. “Supposedly Frankie sold Jamie Principle’s unreleased tapes to DJ International AND Trax at the same time. Then Jamie came out with a record called ‘Knucklehead’ dissing Frankie. After that Frankie went back to New York.”

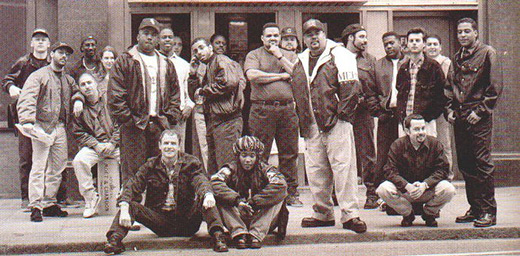

When Rocky Jones at DJ International became convinced by a larger- than-life character named Lewis Pitzele who was helping put a lot of the deals together at the time that Europe was the place to focus on, house poured into Britain with London Records putting the first compilation of early DJ International material out. As the press bandwagon rolled into action the 86 Chicago House Party featuring Adonis, Marshall Jefferson, Fingers Inc and Kevin Irving toured the UK’s clubs. Trax took a little longer. Adonis: “Trax was meant to be a bullshit label for all the dirty, raggedy records Larry Sherman didn’t give a shit about. You know, labels were always trying to do radio stuff, but Trax became popular after ‘No Way Back’ and ‘Move Your Body’ and all those tracks.” It was DJ International and London who notched up the first house hits, first with Farley ‘Jackmaster’ Funk’s ‘Love Can’t Turn Around’, a cover of the old Isaac Hayes song with camp wailer Daryl Pandy on vocals which reached Number 10 in September 1986, and then a record that spent months gestating in the clubs before it was finally catapulted to Number One in January 1987 – Jim Silk’s ‘Jack Your Body’. The Americans were gob smacked. Their underground club music was going mainstream four thousand miles from its home. But it was no surprise that Steve Hurley was behind the track, which hit the top despite only having three words – the title. Even then he was the one with the commercial touch. It wasn’t a terribly original record – the bassline was from First Choice’s ‘Let No Man Put Asunder’, but it summed up the mood of jack fever. All of a sudden the word ‘Jack’, which originally described the form of dancing people did to house, was everywhere ‘Jack The Box’, ‘Jack The House’, ‘Jack To The Sound’ ‘J-J-J-J-JJack-Jack-Jack-Jack’. It was the stutter sample on the ‘J’ that took the word into legend. Vaughan Mason’s Raze, who’d quietly been doing stuff out of Washington DC burst into the clubs and then followed Jim Silk into the charts with ‘Jack The Groove’. And garage? New York simply couldn’t match the energy flowing out of Chicago but there was little doubt that the music was developing simultaneously. The Jersey garage sound, boosted by Tony Humphries (who’d also been on the radio since 1981) at Newark’s Zanzibar Club, was beginning to take shape with Blaze but the New York club sound was defined at the time by Dhar Braxton’s ‘Jump Back’ and Hanson & Davis’ ‘Hungry For Your Love’ which borrowed heavily from the Latin freestyle sound but echoed the energy of house. And over in Brooklyn, producers like Tommy Musto working for the Underworld/Apexton label were developing a different style again, one that like Chicago seemed to take its roots as much from Eurobeat as from Black music, though the mood and tempo was strictly New York.

1987

While Chicago stole the thunder in 1986, other cities not only in the United States but across the world had either been absorbing house or working on their own thing, biding their time. One record from New York served a warning shot that the city was gearing up for some serious action – ‘Do It Properly’ by 2 Puerto Ricans, A Blackman and A Dominican. ‘Do It Properly’ was essentially a bootleg of Adonis‘ ‘No Way Back’ with loads of samples and a great electronic keyboard riff squeezed in to it and the first in a long, long line of New York sample house tracks. Its producers were one Robert Clivilles and David Cole, helped by another guy called David Morales. After that some kid in Brooklyn called Todd Terry made a couple of sample tracks with a freestyle groove for Fourth Floor Records by an act he called Masters At Work.

But the sound that was really taking shape in New York and New Jersey was a deep style of club music based on a heritage that had its roots firmly in r’n’b. Though there were some superb deep, emotive instrumentats like Jump St. Man’s ‘B-Cause’, the emphasis was on songs, which came with Arnold Jarvis’ ‘Take Some Time’, Touch’s ‘Without You’, Exit’s ‘Let’s Work It Out’ and a record on Movln, a new label run from a record store in New Jersey’s East Orange – Park Ave’s ‘Don’t Turn Your Love’. Ironically, as the first garage hits began to appear, The Paradise Garage – {ln:Larry Levan (1954-1992) – Remembering a Legend…. ‘Larry Levan} had already left – closed, but the vibe carried on with Blaze, who recorded ‘If You Should Need A Friend’ and Jomanda, both of whom teamed up with new New York label Quark.

Echoing the need for vocals in house music, deep house began to take hold in Chicago. Following Marshall Jefferson’s lush productions, the record that defined deep house was the Nightwriters’ ‘Let The Music Use You’, mixed by Frankie Knuckles and sung by Ricky Dillard, a record that a year later was to become one of the anthems of the UK’s Summer Of Love. And it didn’t end there. Kym Mazelle launched her career with ‘Taste My Love’ and ‘I’m A Lover’, while Ralphie Rosario unleashed the monstrous ‘You Used To Hold Me’ featuring the wailing tonsils of Xavier Gold. Then there was Ragtyme’s ‘I Can’t Stay Away’, sung by a guy who sounded a a little like a new Smokey Robinson – Byron Stingily. Soon after, Ragtyme, who also made an extremely silly innuendo track called ‘Mr Fixit Man’, mutated into Ten Clty. But Chicago’s excursion into songs wasn’t only characterised by uplifting wailers. There was another side, led by the weird, melanchoty songs of Fingers Inc and beginning to show itself in other minimalist productions like MK II’s ‘Don’t Stop The Music’ and 2 House People’s ‘Move My Body’. By 1987, though house was no longer a tale of two cities. The virus was taklng hold elsewhere as clubbers, DJs and producers worldwide became exited by the new music.

It was obvious that Britain, which had already seen a massive boom in club culture in the mid-eighties as the increasingly racially integrated urban areas turned to Black music in favour of the indigeonous indie rock music, would eventually get in on the act. Though acts like Huddersfield’s Hotline, The Beatmasters from London and a handful of others who included DJs Ian B and Eddie Richards had been trying to figure things out, the first British house track to really make any noise came from a partnership that included a DJ from Manchester’s Hacienda, one of the very first clubs in Britain to devote whole nights to house music – Mike Pickering. With its funk bassline and Latin piano riffs, T-Coy’s ‘Carino’ busted out all over, particularly in London at previously rap and funk clubs like Raw. But with the open nature of the UK pop charts compared to Billboard which was an impossibly tough nut to crack for small labels marketing new music, it was inevitable that the sound would be commercialised. ‘Pump Up The Volume’ by M/A/R/R/S was a rather lightweight record based on a house beat with a number of clever (at the time) samples but it worked like crazy on the dancefloor and it wasn’t long before club support propelled it into the charts, where it held Number 1 for an incredible three weeks. Also in the top ten at the same time was another record that had broken out of Chicago – the House Master Boyz’ ‘House Nation’. The marketability of house – or pophouse – in the UK became gruesomely apparent with the advent of the ‘Jack Mix’ series, a number of hideous stars-on-45 style megamixes of all the house hits.

Things were progressing in a much more underground fashion back in the States. A few guys in particular who’d been noticed hanging out in Chicago and checking the scene came from a city just a couple of hundred miles away Detroit. One of them, Juan Atkins, had been making records since the early eighties under the moniker Cybotron which specialised in spacey electro-funk fired by the Euro rhythms of Kraftwerk. But progress had been slow and electro had already fused with rap. By 1985 Atkins’ sound was beginning to change with records like Model 500’s ‘No UFO’s’, which bore more than a passing resemblance to the new sounds emanating from their neighbouring city. Two other guys who had been to school with Atkins, and who shared his passion for European music were also beginning to experiment with making tracks and heartened by what they heard coming out of Chicago, set to work Their first tracks, X-Ray’s ‘Let’s Go’, produced by Derrick May and Kevin Saunderson’s ‘Triangle Of Love’ by Kreem weren’t classics by any stretch of the imagination but it didn’t tahe them long to hit full power. Kevin came out with ‘Force Field’ and ‘Just Want Another Chance’, and Juan pressed on with Model 500’s ‘Sound Of Stereo’ but it was Derrick who really hit the button with Rhythim Is Rhythm’s ‘Nude Photo’, ‘Kaos’ and ‘The Dance’, all of which were immediate hits on the Chicago scene, and the latter a record that was to be thieved and sampled again and again for years to come. The Belleville Three, as they became known after the college they attended, made an amusing trio with Kevin as the regular guy, Derrick as the fast-talking nutter and Juan as the laid-back smokehead, but there was more to techno than that. Two other producers who helped forge the different sound were Eddie Fowlkes and Blake Baxter. It was faster, more frantic, even more influenced by European electrobeat and severed the continium with disco and Philadelphia, taking only the space funk basslines of George Ctinton from Black music. They called it techno.

But Chicago was also beginning to head off into another direction, the most frenetic form of house yet. It was started by two crazy tracks that Ron Hardy had been pumping at the Music Box and it was going to be perhaps the most important stage of house so far. It was acid.