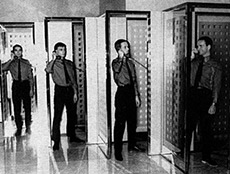

The subsequent marshalling, in revolutionary red and black, of the dynamic diagonals of the Russian constructivist El Lissitzky for the cover of The Man-Machine was a further brilliant stroke which carried all the paradoxical utopian promise and totalitarian threat of the modernist notion of ‘machine art’ which they were effectively resurrecting. The album’s pristine presentation of tracks with titles like ‘Neon Light’, ‘Spacelab’, ‘The Robots’ and (most pertinently) ‘Metropolis’ drives home its theme of antique modernity: these are all old, nostalgically recalled visions of the future, polished and shiny with the awed glow of conviction, before the notion of modernism began to rust.

The subsequent marshalling, in revolutionary red and black, of the dynamic diagonals of the Russian constructivist El Lissitzky for the cover of The Man-Machine was a further brilliant stroke which carried all the paradoxical utopian promise and totalitarian threat of the modernist notion of ‘machine art’ which they were effectively resurrecting. The album’s pristine presentation of tracks with titles like ‘Neon Light’, ‘Spacelab’, ‘The Robots’ and (most pertinently) ‘Metropolis’ drives home its theme of antique modernity: these are all old, nostalgically recalled visions of the future, polished and shiny with the awed glow of conviction, before the notion of modernism began to rust.

“The music, the photos and lyrics, for us it was like a holistic artform,” explains Hütter. “And today, with video and computer images, it’s moving more and more in this direction. We think that the artforms are not at all as divided as they appear to be: you can read music, speech has a musical melody, phonetics are musical sounds, cars can sing as in ‘Autobahn’. So our idea was a mixture of all these things.”

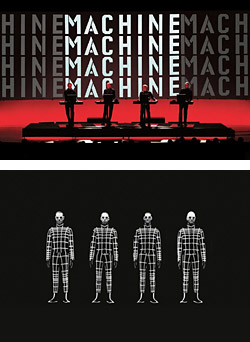

Their idea, and their taste, extended to every aspect of their artwork. At the launch party for The Man-Machine, they hosted (along with their dummy lookalikes) a reception in a chic club atop Paris’ Montparnasse Tower, where their music soundtracked, with a creepy aptness, Russian expressionist silent films. In live shows, meanwhile, they utilised the strength of symmetry, with the two drummers busying themselves at their pads side-by-side stage centre, and Ralf and Florian in three-quarter profile at the sides, each member standing behind their own neon-signature box, while four screens suspended above showed identical images, and banks of coloured fluorescent tubes added their own ghostly pallor to proceedings. At one point, the drummers would position themselves inside a box framework and perform semaphore signals, their hands breaking photo-electric beams to activate the drum sounds. For a group that barely moves at all on-stage, they are one of the most rivetting live spectacles of the age.

They are quick to deny, however, that their live shows are simply note-perfect representations of the recorded versions. Unlike more recent computer-controlled rock concerts, in which every last little ad-lib and ‘instinctive’ moment is carefully pre-sequenced, Kraftwerk long ago took pains to build into their performances opportunities for the improvisation with which they started their career.

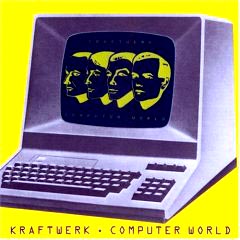

“The compositions on our albums are written like film scripts,” explained Hütter at the time of Trans-Europe Express. “We act out certain sequences, certain scenes, and they come out differently in different cities. In a story like ‘Autobahn’ there are points where we start together and then improvise until we come back together at a certain point.” By the time of Computer World (1981), they had even managed to draw the audience into their improvisation, handing out pocket calculators and encouraging fans to play along: for a band with such supposedly totalitarian overtones, this was more democratic than the average Sham 69 gig.

“The compositions on our albums are written like film scripts,” explained Hütter at the time of Trans-Europe Express. “We act out certain sequences, certain scenes, and they come out differently in different cities. In a story like ‘Autobahn’ there are points where we start together and then improvise until we come back together at a certain point.” By the time of Computer World (1981), they had even managed to draw the audience into their improvisation, handing out pocket calculators and encouraging fans to play along: for a band with such supposedly totalitarian overtones, this was more democratic than the average Sham 69 gig.

And if the audience didn’t want to play, well, the machines could just play themselves. “We play the machines, but the machines also play us,” claims Hütter. “The machines should not do only slave work, we try to treat them as colleagues so they exchange energies with us.” The old saw about the guitar being a more emotional instrument than the synthesizer, meanwhile, received the shortest of shrifts: “We feel that the synthesizer is an acoustic mirror, a brain analyser that is super-sensitive to the human element in ways previous instruments were not, so it is really better suited to expose the human psychology than the piano or guitar.”

Kraftwerk’s is, however, a finite art, doomed by its very perfection to diminishing returns: as their painstakingly devised glacial tones were increasingly sampled by a new generation of electronic composers, their own output dwindled away to a trickle. In the 16 years since Computer World, they have released just one new album (the patchy Electric Cafe), one 12-inch single (‘Tour De France’), and a remix album, The Mix, in which choice selections from their oeuvre were overhauled and given new rhythm motors, like vintage cars being refurbished by audio mechanics.

In 1983, an album called Technopop was slated for release: EMI had received artwork for it, and had even allotted it a catalogue number, but after several postponements, it disappeared completely from the release schedule, with no explanation. A track of the same title appeared on 1986’s Electric Cafe, prompting speculation that it may be the same LP in different guise, but the group’s extreme reclusiveness has left the abandoned album as a lingering mystery. What seems increasingly probable, however, is that their legendary perfectionism has set almost impossible standards for them to follow, while their obsessive self-sufficiency — they’ve turned down offers to collaborate with David Bowie, Elton John and even Michael Jackson — has left them musically isolated.

Hütter explains their minimal release rate through the ’80s and ’90s as largely down to studio renovation. “Our instrument is really Kling Klang Studio, and we rebuilt it completely as a digital studio, which we felt was necessary to update our music,” he told me in 1991.” So we spent a lot of time inventing and engineering some of the instruments, and working on visuals. It’s not just about music, it’s engineering and art and music all combined. Computer World was the last fully analogue album we did; Electric Cafe was a mix of analogue and digital elements. By The Mix, we were working completely digitally.” Others claim that Hütter’s fanatical dedication to cycling — he’s ridden most, if not all, of the famous stages of the Tour De France, and is rumoured to pedal 200 kilometres a day — leaves him little time for working on music.

Their notoriously slow working process — every last detail is apparently agonised over for days, even weeks — took its toll on Wolfgang Flur and Karl Bartos, who left while Ralf and Florian were working on The Mix. The painstaking digitisation of all their old analogue sounds, purely to reconstitute them in slightly different versions of the old songs, must have seemed a less than satisfying way of spending five years, particularly since the percussionists were only peripherally involved in the project.

Their notoriously slow working process — every last detail is apparently agonised over for days, even weeks — took its toll on Wolfgang Flur and Karl Bartos, who left while Ralf and Florian were working on The Mix. The painstaking digitisation of all their old analogue sounds, purely to reconstitute them in slightly different versions of the old songs, must have seemed a less than satisfying way of spending five years, particularly since the percussionists were only peripherally involved in the project.

This was itself a signal of a much deeper rift in the group, for despite their stalwart work over the past five or six albums, Flur and Bartos were still effectively second-class cogs in the Kraftwerk machine, to which Ralf and Florian continued to hold the ignition keys. It wasn’t so much the usual dissension over composer’s royalties — Karl Bartos, in particular, had become increasingly involved in composition, co-writing most of the Computer World album with Hütter — so much as the pervasive inertia of the situation.

Virtually alone among pop groups, Kraftwerk have never employed a manager, Ralf and Florian making decisions on an ad hoc basis, a process made more difficult by their perfectionist reluctance to delegate duties to outside parties. (When William Orbit remixed ‘Radio-Activity’ for a single, Ralf Hütter visited him in London — twice — to check how work was progressing.) Without an outside manager to direct their career, Kraftwerk’s inclination was to let things ride, turning down offers and opportunities, and gaining a reputation for not even responding to their own record company’s enquiries. They have never collaborated with anyone, nor remixed any other artist’s work. And as the ’80s ground on, it seemed that they had effectively ceased working with themselves, too, preferring to let reclusive inaction deepen the band’s growing mystique.

For Bartos, the frustration was unbearable: “I can remember saying to Ralf, ‘It’s like I have this Jumbo Jet in the garden, but it never takes off,'” he told Pascal Bussy. “All those people who wanted to work with us, and we never even did a soundtrack. We could have crossed over, become a big, big selling band. But there was never any management, not even on a small level, like two or three people. There was no telephone, no fax, nothing And in this business, if you need five years to put out a record, then people forget about you.” Bartos subsequently started his own group, Elektric Music, while Flur set up an interior design company with former Kraftwerk visual director Emil Schult. (Their duties in Kraftwerk were assumed, on the live tour that followed the release of The Mix, by Kling Klang Studio engineers Fritz Hilpert and Henning Schmitz; they will also play at Kraftwerk’s eagerly anticipated Tribal Gathering performance at Luton Hoo on May 24, 1997.)

For Bartos, the frustration was unbearable: “I can remember saying to Ralf, ‘It’s like I have this Jumbo Jet in the garden, but it never takes off,'” he told Pascal Bussy. “All those people who wanted to work with us, and we never even did a soundtrack. We could have crossed over, become a big, big selling band. But there was never any management, not even on a small level, like two or three people. There was no telephone, no fax, nothing And in this business, if you need five years to put out a record, then people forget about you.” Bartos subsequently started his own group, Elektric Music, while Flur set up an interior design company with former Kraftwerk visual director Emil Schult. (Their duties in Kraftwerk were assumed, on the live tour that followed the release of The Mix, by Kling Klang Studio engineers Fritz Hilpert and Henning Schmitz; they will also play at Kraftwerk’s eagerly anticipated Tribal Gathering performance at Luton Hoo on May 24, 1997.)

Ironically, the suspended trajectory of Kraftwerk’s career-curve leaves them in the paradoxical position of being more and more influential as they release less and less music. The ghosts of their work are everywhere: from the early approbation of Bowie to the widespread approriation of their sounds and techniques in the ambient and techno fields, Kraftwerk’s ideas and methods now permeate modern pop more thoroughly than any group since The Beatles. Perhaps the truth of their lengthening silence is that, from their rarefied perspective, every way is down.