But this madness needed a name and a night if it was to really make an impact. Paul Cons, installed as part of the management team since 1986, and struck by the fact that you couldn’t breathe in the club on a good night, came up with the Hot concept: water, ice pops, a swimming pool in the middle of the dancefloor – all fairly standard in the Balearic Islands at the time, but unusual nonetheless for northern England. Hot didn’t last long – from the summer until Christmas `88 – but is perhaps the best-remembered night in the club’s history. Jon Da Silva (who had recently taken Dean Johnson’s place alongside Dave Haslam at the Saturday Wide night after Dean had left, fed up with being pestered for house during his famed Latin break) and Mike Pickering soundtracked the madness. A Guy Called Gerald and Graham Massey of 808 State would turn up, banging on the DJ booth door with tapes of deranged 20-minute acid tracks which were gratefully played in full. Sound effects of thunderstorms and rain were played to underline the insanity. People threw water about and nobody got upset. Minus the tales of pharmaceutical excess, these were times you might want to tell your grandchildren about.

But this madness needed a name and a night if it was to really make an impact. Paul Cons, installed as part of the management team since 1986, and struck by the fact that you couldn’t breathe in the club on a good night, came up with the Hot concept: water, ice pops, a swimming pool in the middle of the dancefloor – all fairly standard in the Balearic Islands at the time, but unusual nonetheless for northern England. Hot didn’t last long – from the summer until Christmas `88 – but is perhaps the best-remembered night in the club’s history. Jon Da Silva (who had recently taken Dean Johnson’s place alongside Dave Haslam at the Saturday Wide night after Dean had left, fed up with being pestered for house during his famed Latin break) and Mike Pickering soundtracked the madness. A Guy Called Gerald and Graham Massey of 808 State would turn up, banging on the DJ booth door with tapes of deranged 20-minute acid tracks which were gratefully played in full. Sound effects of thunderstorms and rain were played to underline the insanity. People threw water about and nobody got upset. Minus the tales of pharmaceutical excess, these were times you might want to tell your grandchildren about.

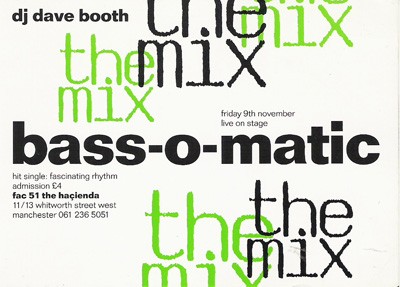

Paul Cons insisted Hot should end on a high and jacked it in with spirits still hovering ten feet above the ground in anticipation. But there was still Zumbar, a retarded cabaret night with fire-eaters and a Wheel Of Fortune. DJ Dave Haslam’s Temperance Club continued too, breaking new ground with an idiosyncratic and open-minded mix of music from James to {ln:Mantronix}, James Brown to The Smiths, which had much to do with a wide-trousered revolution subsequently called baggy and the fact that, from the great Happy Mondays down, all Manchester bands began sounding like “Funky Drummer” played by The Velvet Underground. As a direct result of all this Manchester in general and The Hacienda in particular became under-age tourist attractions.

It was at this time that, during a London photo-shoot lining up the main house offenders for yet another What The Fuck’s Going On? piece, Mike Pickering met Graeme Park – one of the very few DJs outside London who, like Pickering, had become obsessed. The two got on like an acid house on fire, and a few weeks later Mike called the Scots refugee in Nottingham to ask if he could fill in for him while he was away. Graeme jumped at the chance. By the time Mike got back, things had gone so well with Graeme playing on Fridays that it was decided the two would share the night from then on. Graeme, like Jon Da Silva, was a superb and inventive mixer who made his mark on the club.

Relying on what was written at the time, from 1989 onwards, you might have thought The Hacienda did little more than fend off the attentions of the police, watch people get stabbed or die from taking Ecstasy, close, reopen and close again. But we’re talking about eight years to date. And in that time The Hacienda has hosted the ultra-successful gay night Flesh (all the madness of Hot in high heels), let a former fan called Sasha play a few times (queues around the block and then around again), ripped up a well-used dancefloor and sold it (ten quid a piece, you planks), let RoIf Harris perform a can-you-tell-what-it-is-yet painting class, and allowed a proper wedding to take place on stage – giving journalists like me the chance to go on about The Hacienda as a church at great and pretentious length. In a coals-to-Newcastle sensation the club even toured the US, to enthusiastic response from Americans who had techno explained to them in thick north Manchester accents.

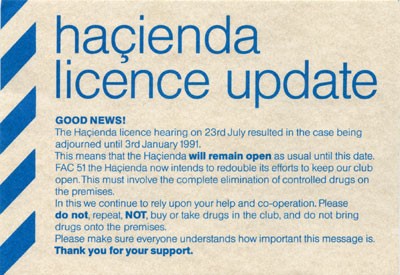

All of this, however, is still overshadowed by the death in July 1989 of teenager Clare Leighton, the victim of an extreme reaction to Ecstasy. Drugs had helped the club plot its peaks and, during the post `88 period, they would shadow its worst times. The comparatively innocent and embarrassingly titled Summer Of Love, a kind of blissful narcotic honeymoon, was soon spoiled by greedy dealers fighting for control of a drug-taking frenzy on a scale none of them had witnessed before. These people didn’t give a shit about acid house – the music was simply a soundtrack to a steep and sudden upturn in their personal fortunes. The Hacienda became the backdrop to their struggle for control and supremacy. During 1990, with Clare Leighton’s death obviously in mind, the police had, under Operation Clubwatch, infiltrated The Hacienda, and seemed to conclude that the dealers, the problem and the club were one and the same. In May 1990 they informed manager Paul Mason of their intention to oppose an upcoming licence renewal. At a hearing on July 23, 1990, having secured the assistance of George Carman DC, the club was granted six months to sort out the problems.

By January 3, 1991, at the postponed hearing, the magistrates decided there had been a “positive change in direction” and renewed the club’s licence. The management themselves decided to reintroduce the original membership scheme to try and keep troublemakers out. Within just a few weeks, on January 30, Tony Wilson announced that the club was closing voluntarily after door staff had been threatened with a gun.

The Hacienda took the time out to apply a new Ben Kelly colour-scheme and install airport-style security measures. It reopened on May 10. By this stage, though, the long-running Saturday with Park and Wainwright, the phenomenal success of Flesh and even RoIf Harris weren’t news enough for the papers, which circled like vultures waiting for stabbings and drug stories. During all of this support came from some strange quarters. One news piece in the Sun called The Hacienda “the most important venue since the Cavern”. New Order, who were never that visible in their financial association with the club, wheeled themselves out to talk and have their pictures taken on the hallowed dancefloor. “Basically,” said Peter Hook, “this place has got to stay. It’s the only place in Manchester that’ll let me in with my jackboots on.”

“The defining moment for me was hearing Rhythm Is Rhythm’s `The Dance’ in about 1987. That was the start of acid house for me – a moment I’ll never forget. I remain eternally grateful to The Hac’s sweaty podiums”

Justin Robertson [ Hac DJ 1990-91, 1994-95]

In 1997, those that took their cues from The Hacienda (step forward, Cream and Hard Times among many, many others) enjoy the ride on the cultural rollercoaster the club helped to create. The Hacienda plays on for ever, like in that Sterling Void song. There’s Pleasure on Fridays (real house and adult techno upstairs, downbeat experiments in the basement), the return of Paul Cons with Freak on Saturdays (fire-eaters, contortionists, Haslam back downstairs and those familiar queues again in a handbag-free zone), and Stone Love (son of Temperance, plenty of under-age snogging in the shadows) to be getting on with.

I asked Tony Wilson a stupid question: can it all happen again? He replied: “Of course it can. Somewhere around 1999 to 2001. And it probably won’t have a thing to do with house music.” And of course he’s right. And the music will change (I’m sure you’ll join me in hoping we’re not diving in swimming pools to trip hop come the millennium), but the building will be there for it – heading for a twentieth birthday – still fighting, still breathing, still giving a damn.

And Rob Gretton will be perched in his favourite ogling spot (“the upstairs lighting booth”, if you must know), confirmed as a bona fide house hero alongside Farley, Marshall, Frankie and the rest of them if you want to start adding it all up.

Musical history tour:

Five certified Hacienda classics

Klein and MBO“Dirty Talk” Released pre-house, this Italian electro-disco curio only really made sense after the Chicago invasion. It is impossible to tire of this record and its handclap crazy charm.

Mantronix“Bassline” In spite of MC Tee – probably the worst rapper in history – “Bassline” is a truly groundbreaking record, which signalled a whole era of hip hop tracks (Eric B, Roxanne Shante etc, etc) designed primarily as dance aids.

Dee-Lite “Wild Times (Derrick May Mix)” This Dee-Lite are not the bri-nylon funkateers from New York but some pony combo whose cliche-filled house record was dragged into the future by Derrick May. This is now rightly regarded as a Rhythim Is Rhythim record Gwen Guthrie “Seventh Heaven” At the time this just seemed like something made by aliens sent down to earth to have a vocal added. A truly startling record.

Salt City Orchestra“The Book” Miles Hollway and Eliot Eastwick used to work behind the bar at The Hacienda. Then they put together this hero-eclipsing, fundamentalist, spooked-out classic which takes the American idea and puts its fingers in a wall socket.