KARLHEINZ Stockhausen, who has died aged 79, was one of the great visionaries of 20th-century music. He was fond of quoting Blake’s lines “He who kisses the joy as it flies, lives in Eternity’s sunrise”; and like Blake, the pursuit of his vision led him down strange, and often awkward paths. The results earned him a reverence among a cult following which is unique among 20th-century composers; but they also earned him a fair amount of ridicule. Roger Scruton’s memorable judgment, that Stockhausen “is not so much an Emperor with no clothing, but a splendid set of clothes with no Emperor” sums up the sceptical view, which in Anglo-Saxon countries has become the dominant one since the 1970s.

KARLHEINZ Stockhausen, who has died aged 79, was one of the great visionaries of 20th-century music. He was fond of quoting Blake’s lines “He who kisses the joy as it flies, lives in Eternity’s sunrise”; and like Blake, the pursuit of his vision led him down strange, and often awkward paths. The results earned him a reverence among a cult following which is unique among 20th-century composers; but they also earned him a fair amount of ridicule. Roger Scruton’s memorable judgment, that Stockhausen “is not so much an Emperor with no clothing, but a splendid set of clothes with no Emperor” sums up the sceptical view, which in Anglo-Saxon countries has become the dominant one since the 1970s.

When Stockhausen was 18, and a music-student in war-devastated Cologne, he read Hermann Hesse’s The Glass Bead Game. This crystallised the conviction, already forming within him that “the highest calling of mankind can only be to become a musician in the profoundest sense; to conceive and shape the world musically.” Stockhausen had reason enough to avert his eyes from the world as it was. His early life was tormented by Nazism and the war it had unleashed. When he was six years old his mother had been taken into an insane asylum; nine years later she was legally killed, one of the victims of the Nazis enforced euthanasia policy. Meanwhile his father had become an enthusiastic Nazi, and eventually fought on the Eastern front, where he went missing and was presumed dead. Stockhausen recalled how as a boy he heard marching songs played incessantly on the radio; an experience which left him with an abiding hatred of regular repetitive rhythms in music. Not all his early experiences were negative ones. The boy was profoundly impressed by the Catholic ritual of rural Germany, where his father had been a schoolteacher, the Easter procession of young girls was recalled, 45 years later, in Act 2 of Montag, one of the cycle of seven linked music-dramas named Licht (Light) to which Stockhausen devoted the last third of his life.

All this might create the impression of a musical crank with a taste for electronics and vast stage spectacles. What is often forgotten, in the noisy polemics around Stockhausen, is the fact that his visions were put into practice with a colossal speculative and practical intelligence, which earned him the respect and enthusiasm of musicians as diverse as Boulez and the Beatles.

All this might create the impression of a musical crank with a taste for electronics and vast stage spectacles. What is often forgotten, in the noisy polemics around Stockhausen, is the fact that his visions were put into practice with a colossal speculative and practical intelligence, which earned him the respect and enthusiasm of musicians as diverse as Boulez and the Beatles.

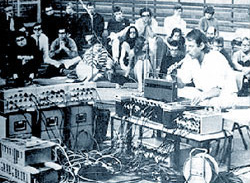

Stockhausen was fortunate in that his speculative turn of mind, and his impatience with inherited forms and vocabulary, caught the mood of the times. Although the Stockhausen of the 1980s seemed a lonely figure, he was not so in the 1950s. As he put it “At the middle of the century . . . an orientation away from mankind began. Once again one looked up to the stars and began an intensive measuring and counting.” We see him, in these pictures of the summer music schools at Darmstadt, as just one of many lean, impoverished, idealistic young composers, indelibly marked by the war, and determined to rework the language of music from scratch. They were all possessed of a self-confidence, and an impatience and scorn of their elders, that seems astonishing in these creatively diffident times. Two older composers they made an exception for; one was Anton Webern, whose rigourous form of serialism was to be an inspiration for them; he, however, was already dead, killed accidentally by a member of the occupying forces in Vienna. The other was Olivier Messiaen, in whose class at the Paris Conservatoire many of these composers came together.

Messiaen’s experiments in extending arithmetical forms of organisation beyond pitch, to embrace rhythm, timbre and dynamics, confirmed Stockhausen in his belief that this was the way forward. But over the next few years he was to take the serial ideas into wholly now areas. Like Ligeti and Boulez, he passed through a “pointillist” phase, in which the texture is splintered into individual notes, and like them, he soon became dissatisfied with it. Several key works of the 1950s, all since confirmed as classics of the century’s music, found a new way of utilising the serial idea, in which the elements to be organised were no longer “points”, but groups of variable length, each defined by certain overall features such as speed, density and range. The title of his most famous (and some would say best) piece, Gruppen, has a marvellous exuberance, in which fantasy and rigour feed off one another.

Messiaen’s experiments in extending arithmetical forms of organisation beyond pitch, to embrace rhythm, timbre and dynamics, confirmed Stockhausen in his belief that this was the way forward. But over the next few years he was to take the serial ideas into wholly now areas. Like Ligeti and Boulez, he passed through a “pointillist” phase, in which the texture is splintered into individual notes, and like them, he soon became dissatisfied with it. Several key works of the 1950s, all since confirmed as classics of the century’s music, found a new way of utilising the serial idea, in which the elements to be organised were no longer “points”, but groups of variable length, each defined by certain overall features such as speed, density and range. The title of his most famous (and some would say best) piece, Gruppen, has a marvellous exuberance, in which fantasy and rigour feed off one another.

By this time Stockhausen had already become the acknowledged leader in what was then a fledgling medium; electronics. In the threadbare studio of the Paris Technical College he worked on a new dream: “I now wanted a structure, to be realised in an Etude, that was already worked into the micro-dimension of a single sound, so that in every moment, however small, the overall principle of my idea would be present.” He worked on this idea with obsessive thoroughness, later recalled by {ln:Pierre Schaeffer & Pierre Henry : Musique Concrète ‘Pierre Schaeffer}, the director of the studio: “He absolutely refused to follow my advice; he did not want any advice at all . . . what I remember is a charming young man who . . . could have been involved in a mutually interesting exchange of ideas, but just did not want to listen to any rational view of things and clung on to his Study on One Sound with a perfectly natural sense of ambition.”

As a critique of Stockhausen’s approach, this seems wide of the mark. The real problem about Stockhausen’s approach was not that it was irrational, but that it was altogether too rational. Like Ptolemaic astronomy, it was wedded too much to ideal abstractions, and could not mesh with the real world without a vast sense of strain. It also needed much special pleading on the part of the listener, a problem epitomised in the conclusion of Schaeffer’s story: “. . . he got down to splicing and came back very happy, and we said, ‘Well, fine, let’s have a listen to it.’ So we played back the tape – and all you heard was ‘Schuuut’. That was Stockhausen’s sound study: a sort of ‘Schuuutt’. He was terribly pleased with it . . .”

This anecdote echoes the accusation levelled at Stockhausen’s music as a whole, that the vast ideas it contains often sound chaotic or merely ugly. He was accused, by Hans Keller in particular, of having no ear (an accusation also levelled against that other mystical rationalist of music, Iannis Xenakis). It is certainly true that Stockhausen’s music never has the exquisitely gorgeous sonorities of Boulez, or the hypersensitive shadings and nuances of Ligeti. What he has in abundance is the ability to focus a long and apparently rambling argument in a sudden, blazingly dramatic gesture. Stockhausen’s music contains some of the great, defining aural images of 20th-century music, on a par with the flute that opens Debussy’s L’après-midi d’un Faune or the upward swoop that ends Schoenberg’s Erwartung. Take for example the closing pages of Gruppen, where apocalytic brass chords are teased from one orchestra to another over the listener’s head; or the moment in Kontakte where an electronic wail descends into the depths and turns magically into a series of pulses. This amazing piece was created by the same laborious cut-and-splice techniques which had left Schaeffer so unimpressed in 1951, only eight years later, they yielded what is still felt to be a masterpiece of the electronic medium. That Stockhausen could achieve such a result with such primitive means (as they now seem), in the face of scepticism from his professional elders, and constant hostility and incomprehension from audiences, is a tribute to his strength of character and his unwavering visionary purpose. The obvious fact that it could not have been achieved without a high degree of pragmatism, of “making do,” is often overlooked. The visionary in Stockhausen was always allied with the meticulous calculator and the practical musician and studio technician. “Don’t give me ideas, give me sounds,” he would say to his composition students. This gives the lie to another frequent criticism of Stockhausen; that he was the prisoner of rigid, “mathematical” systems of composing. On the contrary, he was always finding ways of letting spontaneity in. In all his pieces there occurs a little bit of devilment that does not actually belong in the construction of the whole thing. “It shows that I can always allow myself to escape from my own house, from my own system . . .”

That urge became stronger with the years, fueled by his contact with oriental music and religion. As his fame grew, Stockhausen began to travel the world on concert tours. The encounters he had on these tours with Indian and Japanese culture reawakened the religious streak which had lain dormant in Stockhausen since his childhood. It led him to reconsider how his overriding aim in music, to achieve an absolute unity, a “oneness” of form and material, might be brought about. Previously this had been achieved by constructive means, in the studio; now meditation, improvisation, and a willingness to allow the “voices” of the world to speak in his music became more important.

One of the first fruits of this new inclusiveness was Telemusic in which Stockhausen uses electronics to create a kind of world music. Among the electronic sounds we catch fugitive glimpses of Japanese monks chanting, folk songs, Christian hymns. This was followed by Hymnen, in which the hymns of the title are national anthems from around the world, electronically transformed, and Stimmung, Stockhausan’s own contribution to flower-power culture. The trend towards spontaneity reached its apogee in 1968 with Aus den Sieban Tagen. These were examples of what Stockhausen called “intuitive music” a kind of group improvization guided by a series of verbal texts. In 1970 came yet another new development, perhaps the most surprising. This was a rediscovery of melody, now conceived as a kind of “formula,” whose components would no longer be simple notes, but types of musical behaviour clustered round a note. This formula would then be expanded over long stretches of time, surounded by the same formula in a smaller form.

One of the first fruits of this new inclusiveness was Telemusic in which Stockhausen uses electronics to create a kind of world music. Among the electronic sounds we catch fugitive glimpses of Japanese monks chanting, folk songs, Christian hymns. This was followed by Hymnen, in which the hymns of the title are national anthems from around the world, electronically transformed, and Stimmung, Stockhausan’s own contribution to flower-power culture. The trend towards spontaneity reached its apogee in 1968 with Aus den Sieban Tagen. These were examples of what Stockhausen called “intuitive music” a kind of group improvization guided by a series of verbal texts. In 1970 came yet another new development, perhaps the most surprising. This was a rediscovery of melody, now conceived as a kind of “formula,” whose components would no longer be simple notes, but types of musical behaviour clustered round a note. This formula would then be expanded over long stretches of time, surounded by the same formula in a smaller form.

By this time Stockhausen was no longer the lean, rather hollow-cheeked and impoverishad composer of the 1950s. He was now something of a celebrity, with a reputation that had penetrated even into rock music circles (his photo appears on the cover of Sergeant Pepper). He had acquired the long hair of a rock musician (but not their appetite for drugs, of which he strongly disapproved) and his domestic menage was becoming ever more extraordinary. By the late 1970s the four children of Stockhausen’s second marriage (to the painter Mary Bauermeister, who by now had parted from him), together with the children of the first marriage, had been joined in Stockausen’s self-designed house at Kurten by two “companions” the flautist Kathinka Paeveer and the clarinettist Suzane Stephens. Both of these, and the composer’s children Markus, Majella and Simon, were to become brilliant exponents of Stockhausen’s music, and in his seven-opera cycle they assumed crucial roles.

By this time Stockhausen was no longer the lean, rather hollow-cheeked and impoverishad composer of the 1950s. He was now something of a celebrity, with a reputation that had penetrated even into rock music circles (his photo appears on the cover of Sergeant Pepper). He had acquired the long hair of a rock musician (but not their appetite for drugs, of which he strongly disapproved) and his domestic menage was becoming ever more extraordinary. By the late 1970s the four children of Stockhausen’s second marriage (to the painter Mary Bauermeister, who by now had parted from him), together with the children of the first marriage, had been joined in Stockausen’s self-designed house at Kurten by two “companions” the flautist Kathinka Paeveer and the clarinettist Suzane Stephens. Both of these, and the composer’s children Markus, Majella and Simon, were to become brilliant exponents of Stockhausen’s music, and in his seven-opera cycle they assumed crucial roles.

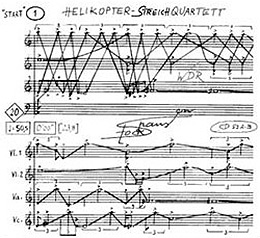

This cycle was begun in Kyoto in 1977, with a notation for the three “formulas” that attach to the three main characters of the cycle. These are Lucifer, Eve and Michael. The whole cycle was a vast creation and redemption myth, in which the dark angel Lucifer battles with, and eventually is vanquished by, the Creator-Angel Michael and Eve, who symbolizes “the rebirth, in music, of mankind.” Three operas would be centred around one character, three around the encounter between two of them, and one would equally involve all three.

The combination of vast mythical ambition with a strict permutational form is absolutely typical of Stockhausen. This is why it makes no sense to divide his career into a rationalist and a mystical phase; both were intertwined from the beginning, and they came together in the serial principle, to which Stockhausen, remained loyal to the end. (This is why his music has absolutely nothing in common with the “religious minimalists,” of the 1990s). In the early 1970s Stockhausen declared that “Serial thinking is something that’s come into our consciousness and will be there forever; it’s relativity and nothing else . . . it’s a spiritual and democratic attitude toward the world.” That may have been true of him, but it certainly hasn’t been true for the rest of the musical world, which has for the most part turned its back not just on serialism, but on the whole modernist enterprise. Like Boulez, Stockhausen had a contempt for post-modernism, and for much the same reasons; it was nostalgic, lazy, parochial. But whereas Boulez’s activities as conductor and dirigeur of French musical culture kept him before the public eye, Stockhausen retreated from view. Every few years another mystical music-drama emerged from Kurten, to be greeted with a mixture of awed puzzlement and amusement; meanwhile a new generation of “post-modern” composers arose for whom Stockhausen was anathema.

Is it true, as the more extreme of these young historicists claim, that Stockhausen is nothing but a symptom of an aberration in the history of music? If one based one’s view of his achievement on Licht, so often theatrically naive and musically otiose, the answer might well be yes. But taken as a whole, Stockhausen’s achievement must be the most fertile in ideas, if not of perfectly achieved works, of any composer of the 20th century. Those ideas are strenuous, boldly speculative, and high-minded in a way that doesn’t really suit our more cautious age; but when the time to explore and dream comes again, Stockhausen’s music will be waiting for it.

Karlheinz Stockhausen, composer, born August 22, 1928; died December 5, 2007