The Roland SH101, released around 1982, was designed to be accessible and affordable; it’s also compact and lightweight with a very easy layout. If you’re not creating wild sounds within five minutes of applying power, then you’re in the wrong business. All controls are stretched across the front panel above the 32-note F-C keyboard.

From the left:

• LFO (Low Frequency Oscillator): sine, square, random waveforms and noise can be used to modulate the VCO, pulse width and/or VCF; doubles as an arpeggiator/sequencer clock.

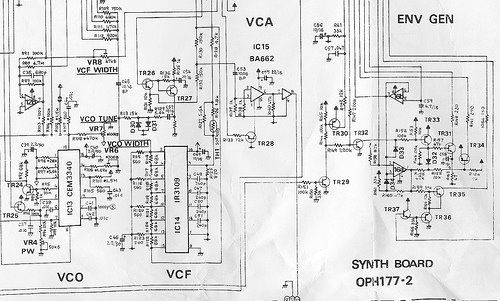

• VCO (Voltage Controlled Oscillator): one only, with pulse (variable square wave) and triangle waveforms, a range of 16, 8, 4 and 2 feet (at 8 feet, the lowest C on the keyboard corresponds to middle C), and a white noise source (hooray: sound effects!). The real treat here is the sub-oscillator (one or two octaves below), which really adds power to the 101’s single oscillator operation.

• VCF (Voltage Controlled Filter): this is where you really start to define the character of the sound. Cutoff frequency is fully variable from 0Hz to 20kHz, and resonance is variable up to self-oscillation, providing a pure sine wave or tweeter damage, depending on the circumstances. Keyboard tracking is also available.

• VCA (voltage controlled amplifier): normally controlled by the EG, but can be controlled by a simple gate.

• ENV (envelope generator, or EG): a basic Attack, Decay, Sustain, Release device that defines the contour of the finished sound. A switch lets you choose whether the EG will retrigger when you play a new note or finish in its own time.

The SH101 marks an early appearance for Roland’s all-in-one pitch bend/mod wheel. A variable portamento control can be set to kick in only when you play legato, giving a smooth, musical effect. Also on board are an arpeggiator and 100-step sequencer, which isn’t as limited as you’d think. The arpeggiator works in down, up, or up & down modes; a hold button freezes a pattern of notes, and the transpose button lets you start a pattern in C, say, and transpose it in real time to suit your track. Connections include gate and control voltage ins/outs, and external clock in. Note that arpeggiator and sequencer info isn’t output, and an external keyboard can’t be used to control the sequencer, arpeggiator or transpose function, although portamento and pitchbend aren’t disabled when played externally.

That’s what it’s got — what does it do? Well, whether for providing thundering, sub-oscillator bass or exciting the ether with new-agey, whispery, pipe-like sounds, the SH101 has carved its own niche. For rave and dance in general, you can’t go far wrong — bleeps and filter sweeps simply ooze from its modest grey case. The VCF is wicked; a good trick is to set up a bass patch with high resonance and low cutoff frequency, and modulate it with random LFO while using the arpeggiator or sequencer. This produces a bleepy, bloopy, tight, rhythmic sound that can really give a track some drive: notes are alternately sub-bass or high squeak in feel, and the randomness of the LFO makes for completely unpredictable results; use with timed delays. Sync’ing the arpeggiator or sequencer externally (I use the clock output from Kenton’s Pro 2 MIDI-CV interface) allows the LFO to be free-running; modulation effects that are out of sync are also useful.

In general, SH101s have very stable tuning — mine can go for weeks before needing a slight tweak. If your SH101 needs recalibration, note that unlike many synths, the necessary controls aren’t accessible externally. You may also need service data. Price-wise, new SH101s retailed for around USD1000; you could expect to pay up to £200 for a good example these days. But don’t get conned into paying tons more for one of the ‘rare’ alternative colours, unless you simply must have an SH101 in red.

Other machines offer more comprehensive controls, more oscillators, more modulation facilities and more potential power, but the SH101 hass got character, it’s got balls, and it’s somehow capable of sounds that are unobtainable elsewhere. Indispensable.

One prominent option for the SH101 was the MGS1 modulation grip set; this provided the user with a strap, two strap buttons and a modulation grip. The (left-handed) grip gives you access to pitch bend and an LFO modulation switch — perfect for competing with guitarists on stage. You may now be formulating a question regarding the power supply: I’ll stop you in mid-formulation and tell you that the SH101 can also run from batteries, and is still not heavy; the only dangling lead you’ll have is the audio cable.

The SH101’s circuitry not only forms the basis for the most ravey MC202, but can also be found in modular form. The CMU810 was a part of Roland’s pre-MIDI Compumusic system; it’s essentially an SH101 in a trendy, sloping box that matches the rest of the system. It lacks sequencer and arpeggiator, but adds a very useful CV filter input. It’s an excellent little unit, and very compact, although almost impossible to find.