Although experiments in recording sound onto magnetic tape began at the turn of the century, it wasn’t until the 1940’s that the first portable magnetophone tape recorder was invented in Germany. After the war, this technology was confiscated by the Allies and introduced to North America and other European capitals for research throughout the post-war years. The tape recorder’s popular fate was sealed; but even when commercial success soared in the 1950’s and 1960’s, the device was still intended to reproduce music, not to create it. However, unbeknownst to the music establishment at that time, groups of pioneering alternative music composers in various parts of the world had other ideas.

Electronic music experiments in Europe put cities like Paris, Cologne and Milan ahead of their English and American counterparts in London, New York and San Francisco, who followed closely behind with revolutionary synthesizers.

For this reason I have singled out five of the most important studios, divided into the two above-mentioned geographical areas: Europe: 1940 – 1960; and North America / UK: 1950 – 1970. This is obviously a generalization of recording developments that on the contrary, manifested randomly and sporadically around the world from the mid-1930’s until the late 1970’s. For this reason there is a third section called Other Innovators which is devoted to various electronic music studios that helped blaze trails in the early years of recording/composing techniques. Because of these radical challenges to the mainstream music institutions of that generation, we are able to enjoy the established freedom and uniqueness of electronic music today. Indeed, current modern technology enables almost anyone to build their own electronic music studio at home.

These are the grandfathers of our modern precision recording studios. It should be noted that many other smaller or lesser known electronic music studios were vital in their exploration, as a bit of research will certainly divulge. But remember, it was not until the mid-1950’s that the term “electronic music” was even recognized! Numerous works from these studios have been re-mastered digitally for CD release –check it out.

– Europe: 1940 – 1960

• Cologne, Germany: electronic music studios @ NWDR – Nordwest Deutscher Radio Rundfunk

• Paris, France: Groupe de Recherches Musicales @ RTF – Radiodiffusion/Télévision Française

– North America / UK: 1950 – 1970

• London, England: EMS – Electronic Music Studios Ltd.

• New York / Princeton, U.S.A.: CPEMC – Columbia-Princeton Electronic Music Center

• San Francisco, California: SFTMC – San Francisco Tape Music Center

– Other Innovators

Europe: 1940 – 1960

• Cologne, Germany: the electronic music studios @ NWDR – Nordwest Deutscher Radio Rundfunk

These studios were founded in 1951 by and Herbert Eimert, Robert Beyer and Werner Meyer-Eppler following their successful radio broadcasts of electronic music with occasional guest lecturers (ex: Friedrich Trautwein). {ln:Karlheinz Stockhausen: Electronic Music’s Enfant Terrible ‘Karlheinz Stockhausen} consequently joined the team (eventually becoming director) and many other alternative music composers spent time there, including Edgar Varèse, John Cage, György Ligeti and Luciano Berio. A major point of interest is the group’s creation of pure electronic music, or “electroacoustic” music during a time when playback music – vinyl or otherwise – was still largely “concrete”. It is believed that Eppler first used the term “electronic music”. Closely associated with the NWDR studios in the 1950’s were the Darmstadt meetings of electronic and avant-garde music freaks with seminars, concerts, lectures and other multi-media “happenings” known as the Darmstadt Circle or Darmstadt School. Visionists like Olivier Messiaen. Stockhausen, Luigi Nono and Pierre Boulez were part of these summer “Ferienkurse” courses, radically exploring electronic music with true serialist style. The fine-tuning of these ideas was then applied at the studios in Cologne. In these strategic regions of Germany, musical constructivism (“autopoiesis”) was born and history was made.

These studios were founded in 1951 by and Herbert Eimert, Robert Beyer and Werner Meyer-Eppler following their successful radio broadcasts of electronic music with occasional guest lecturers (ex: Friedrich Trautwein). {ln:Karlheinz Stockhausen: Electronic Music’s Enfant Terrible ‘Karlheinz Stockhausen} consequently joined the team (eventually becoming director) and many other alternative music composers spent time there, including Edgar Varèse, John Cage, György Ligeti and Luciano Berio. A major point of interest is the group’s creation of pure electronic music, or “electroacoustic” music during a time when playback music – vinyl or otherwise – was still largely “concrete”. It is believed that Eppler first used the term “electronic music”. Closely associated with the NWDR studios in the 1950’s were the Darmstadt meetings of electronic and avant-garde music freaks with seminars, concerts, lectures and other multi-media “happenings” known as the Darmstadt Circle or Darmstadt School. Visionists like Olivier Messiaen. Stockhausen, Luigi Nono and Pierre Boulez were part of these summer “Ferienkurse” courses, radically exploring electronic music with true serialist style. The fine-tuning of these ideas was then applied at the studios in Cologne. In these strategic regions of Germany, musical constructivism (“autopoiesis”) was born and history was made.

• Paris, France: Groupe de Recherches Musicales @ RTF – Radiodiffusion/Télévision Française

The Musique Concrete concept that was born in these studios is still very much alive today. Beginning in the 1940’s, {ln:Pierre Schaeffer & Pierre Henry : Musique Concrète ‘Pierre Schaeffer and Pierre Henry} had recorded their real-life “found sounds” onto vinyl and were mixing, looping and filtering these organics with traditional music. They also embraced the advent of the tape recorder, which afterwards had them in alignment but not always in agreement with the Cologne/Darmstadt groups. Although Musique Concrète and electroacoustic music may still have their distinguishable differences today, by the late 1950’s avant-garde musicologists were more interested in the application of these new sounds than in their origins. In their exploration, Schäffer and Henry laid legendary groundwork for the future of music sampling. One of the most famous Musique Concrète manifestations was “Poem Éléctronique” composed for tape by the great modernist Edgar Varèse, for the Phillips Pavillion at the Brussels World’s Fair in 1958. Working with architect Le Corbusier and using 425 loudpeakers within the pavillion, bedazzled spectators were treated to coloured visuals and projected images that accompanied the new sound.

The Musique Concrete concept that was born in these studios is still very much alive today. Beginning in the 1940’s, {ln:Pierre Schaeffer & Pierre Henry : Musique Concrète ‘Pierre Schaeffer and Pierre Henry} had recorded their real-life “found sounds” onto vinyl and were mixing, looping and filtering these organics with traditional music. They also embraced the advent of the tape recorder, which afterwards had them in alignment but not always in agreement with the Cologne/Darmstadt groups. Although Musique Concrète and electroacoustic music may still have their distinguishable differences today, by the late 1950’s avant-garde musicologists were more interested in the application of these new sounds than in their origins. In their exploration, Schäffer and Henry laid legendary groundwork for the future of music sampling. One of the most famous Musique Concrète manifestations was “Poem Éléctronique” composed for tape by the great modernist Edgar Varèse, for the Phillips Pavillion at the Brussels World’s Fair in 1958. Working with architect Le Corbusier and using 425 loudpeakers within the pavillion, bedazzled spectators were treated to coloured visuals and projected images that accompanied the new sound.

North America / UK: 1950 – 1970

• London, England: EMS – Electronic Music Studios Ltd. (bottom and top photos)

Throughout the 1960’s the spark generated by the yet underground electronic music craze was shared by many new, aspiring composers, musicians and music scientists. In London, the independently wealthy Russian immigrant Peter Zinovieff founded EMS in 1969, bringing with him the experience from his private studio and a keen interest in the newest electronic music development – computers. In fact, he owned two 12-bit computers, each with 1k of memory. It should be noted that the price tag for one of these computers was in the six digits, filled an entire room and having two was indeed state-of-the-art. Until the company was sold in 1979, they built various electronic instruments and computers for commercial use. The studios were also an active part of the 1970’s progressive rock and disco-synth waves. Pink Floyd used the studios for five of their albums including Dark Side Of The Moon. Other artists in and out of the studios included Brian Eno/Roxy Music, {ln:Kraftwerk}, The Who, Tangerine Dream and {ln:The Roots Of Italo Disco ‘Giorgio Moroder}. Robin Wood, a former member of the orignial EMS team, acquired the company in 1995. Several models of synthesizers are still being produced “made to measure”.

Throughout the 1960’s the spark generated by the yet underground electronic music craze was shared by many new, aspiring composers, musicians and music scientists. In London, the independently wealthy Russian immigrant Peter Zinovieff founded EMS in 1969, bringing with him the experience from his private studio and a keen interest in the newest electronic music development – computers. In fact, he owned two 12-bit computers, each with 1k of memory. It should be noted that the price tag for one of these computers was in the six digits, filled an entire room and having two was indeed state-of-the-art. Until the company was sold in 1979, they built various electronic instruments and computers for commercial use. The studios were also an active part of the 1970’s progressive rock and disco-synth waves. Pink Floyd used the studios for five of their albums including Dark Side Of The Moon. Other artists in and out of the studios included Brian Eno/Roxy Music, {ln:Kraftwerk}, The Who, Tangerine Dream and {ln:The Roots Of Italo Disco ‘Giorgio Moroder}. Robin Wood, a former member of the orignial EMS team, acquired the company in 1995. Several models of synthesizers are still being produced “made to measure”.

• New York / Princeton, U.S.A.: CPEMC – Columbia-Princeton Electronic Music Center

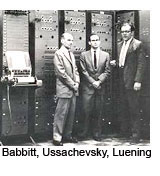

In the early 1950’s on the East Coast of the United States a wave of new music was forming, paralleling the avant-garde movement in Europe. Combining studio efforts in Toronto, Princeton and New York, three composers started the CPEMC in 1951 on the Columbia University campus in New York City: Vladimir Ussachevsky, Otto Luening and Milton Babbitt. These studios boasted the famous RCA Mark II Synthesizer (which is still there) that had an original price tag of 500,000 dollars. Throughout the 1950’s, the center rose to cult prominence and there was regular contact with notables like Stockhausen and Cage. It was all very elitist for a group of people surviving on grants and there were of course many critics examining this “weird” music. But the ideals survived and thrive: in 1996 the center was renamed the Computer Music Center and continues to act as a platform for electronic music artists and students.

In the early 1950’s on the East Coast of the United States a wave of new music was forming, paralleling the avant-garde movement in Europe. Combining studio efforts in Toronto, Princeton and New York, three composers started the CPEMC in 1951 on the Columbia University campus in New York City: Vladimir Ussachevsky, Otto Luening and Milton Babbitt. These studios boasted the famous RCA Mark II Synthesizer (which is still there) that had an original price tag of 500,000 dollars. Throughout the 1950’s, the center rose to cult prominence and there was regular contact with notables like Stockhausen and Cage. It was all very elitist for a group of people surviving on grants and there were of course many critics examining this “weird” music. But the ideals survived and thrive: in 1996 the center was renamed the Computer Music Center and continues to act as a platform for electronic music artists and students.

• San Francisco, California: SFTMC – San Francisco Tape Music Center

Although electronic music was finding artistic outlets on both sides of the North American continent, it was on the West Coast where pioneers Morton Subotnik and Ramon Sender concentrated their experiments. Both founded the SFTMC in 1961 and both came from nearby Mills College Music Department. The rising counterculture of the area was a catalyst for the radical talent pulsating from this group. In 1966, the Tape Center moved to Mills College and most of the original members left. During its lifetime, the center has presented legendary concerts of works by Terry Riley, John Cage, Luciano Berio, Stockhausen and the two founding members Subotnik and Sender. In 1965 they supervised the construction of Don Buchla’s famous Moog-like “Buchla Box” modular synthesizer which played a significant role in the birth of the Minimalist Music movement. Terry Riley and his New York contemporary La Monte Young spearheaded this movement. Thirty years later in 1996, former SFTMC director and composer Pauline Olliveros returned to Mills College, to what is now known as the Center for Contemporary Music.

Although electronic music was finding artistic outlets on both sides of the North American continent, it was on the West Coast where pioneers Morton Subotnik and Ramon Sender concentrated their experiments. Both founded the SFTMC in 1961 and both came from nearby Mills College Music Department. The rising counterculture of the area was a catalyst for the radical talent pulsating from this group. In 1966, the Tape Center moved to Mills College and most of the original members left. During its lifetime, the center has presented legendary concerts of works by Terry Riley, John Cage, Luciano Berio, Stockhausen and the two founding members Subotnik and Sender. In 1965 they supervised the construction of Don Buchla’s famous Moog-like “Buchla Box” modular synthesizer which played a significant role in the birth of the Minimalist Music movement. Terry Riley and his New York contemporary La Monte Young spearheaded this movement. Thirty years later in 1996, former SFTMC director and composer Pauline Olliveros returned to Mills College, to what is now known as the Center for Contemporary Music.

Other Innovators

The University of Toronto Electronic Music Studio was very influential in the progression of the voltage-controlled synthesizer, first built by Canadian Hugh Le Caine in 1955. Le Caine was a close advisor to the studio and composed the legendary “Dripsody” for his new device, which he called the Electronic Sackbut. The piece is based on the sound of a drop of water and became Le Caine’s signature work. Myron Schaeffer also built the first Hamograph at the studio in 1960, which caught the interest of the late synthesizer pioneer {ln:Robert Moog (1934 – 2005): A Tribute ‘Robert Moog}. In Europe, Luciano Berio’s Studio di Fonologia in Milan, Italy became a platform for many rising talents of the time, including John Cage who composed his Fontana Mix there. Berio originally founded the studio in 1955 and used it for experimental work with voice and electronic music, together with his wife Cathy Barberian, the famous “enfant terrible” opera singer. Beginning in the mid-50’s the Siemens Studios in Munich produced electronic music for film, television, radio and theater. Artists such as Pierre Boulez, Werner Meyer-Eppler, György Ligeti, Yannis Xénakis, Karlheinz Stockhausen and Vladimir Ussachevsky were invited there to visit and/or work on compositions. The Netherlands produced significant achievements in electronic music recording: the Phillips Studio and their invention of the portable, cartridge tape recorder in 1963; and the music studio at the University of Utrecht where famous Dutch composers like Henk Badings were experimenting with computer music – in 1969! The Electronic Music Studios in Stockholm and Fylkingen, Sweden were springboards for great Scandinavian avant-garde composers like Leo Nilsson. Founded in the 1960’s the studios sponsored the famous electronic music festivals in Fylkingen which continue today. Lastly, the Institut de Recherche et Coordination Acoustique/Musique in Paris (IRCAM) houses some of today’s most advanced recording studios, utilizing the most up to date equipment and expert know-how in computer music science. Since its inception in 1970 under the directorship of Pierre Boulez (who left in 1992), the institute endures in the new millennium as a major workstation for researchers in new music technology, often in conjunction with the Centre Georges Pompidou.