In the world of electronic music, Kraftwerk are the kings across the water. Despite releasing no new material in over a decade, they continue to wield more influence than any of their Anglo-American peers in the arcane business of bleeps and beats. Scratch a techno whizkid or studio engineer, and nine times out of 10 you’ll find a Kraftwerk fan (the tenth will be too busy sampling them to respond). And it’s not only in the big studios that their influence is felt; in bedrooms and back rooms all over the globe, autodidact musicians are massively in their debt. Most amazing of all, it’s undoubtedly true that without this whitest of white groups, the history of black music in America would have been completely different.

In the world of electronic music, Kraftwerk are the kings across the water. Despite releasing no new material in over a decade, they continue to wield more influence than any of their Anglo-American peers in the arcane business of bleeps and beats. Scratch a techno whizkid or studio engineer, and nine times out of 10 you’ll find a Kraftwerk fan (the tenth will be too busy sampling them to respond). And it’s not only in the big studios that their influence is felt; in bedrooms and back rooms all over the globe, autodidact musicians are massively in their debt. Most amazing of all, it’s undoubtedly true that without this whitest of white groups, the history of black music in America would have been completely different.

When Afrika Bambaataa took Kraftwerk’s ‘Trans-Europe Express’ and ‘Numbers’ and combined them to form ‘Planet Rock’, he set in train (sic) a movement which, as the rappers say, just don’t stop: not only was this effectively the birth of hip hop culture, but in Detroit young black kids like Derrick May, Juan Atkins, Kevin Saunderson and Carl Craig fed on Kraftwerk’s hypnotic rhythms and developed what later became known as techno. In Britain, meanwhile, late ’70s industrialists such as The Human League and Cabaret Voltaire built on Kraftwerk’s breakthroughs, taking the sequenced-synthesizer sound to the furthest reaches of, respectively, pop’s heartland and rock’s avant-garde.

Though Kraftwerk would become internationally famous a few years later for their meticulous hynotic grooves and ‘Showroom Dummies’/’Robots’ personae, they started out as experimentalists in the grand Krautrock tradition, classically trained musicians in revolt against the old ways. The group’s core, Ralf Hütter and Florian Schneider, met while studying piano and flute respectively at a classical conservatory; bored with the restrictions their studies imposed, they found a new fascination in the electronic music which the nearby West Deutsche Rundfunk radio station in Cologne would broadcast late at night.

“We were trained on classical instruments, but we found them too limiting,” explains Ralf Hütter. “In the old days a pianist would have to practise repetitive mechanical exercises eight hours a day just to keep the fingers supple; with our computers, all this is taken care of, and you can spend your time in structuring the music. Practising is no longer necessary — I can play faster than Rubinstein with the computer, so it’s no longer relevant. It’s more about getting closer to what the music is about. It’s thinking and hearing, it’s no longer gymnastics.”

The duo first worked together in The Organisation, a Düsseldorf avant-rock quintet whose only recorded work, the RCA album Tone Float, is one of the rarer Krautrock artefacts. Striking out as a duo in early 1970, Ralf and Florian subsequently set up shop near the city’s main railway station, a small studio with no public access, no receptionist, and no telephone; indeed, reflecting their approach to music, it’s more like a factory than an office. Called Kling Klang, they have remained there ever since.

“Our music has been called ‘industrial folk music’,” acknowledges Hütter. “That’s the way we see it. There’s something ethnic to it; it couldn’t have come from anywhere else. The Berlin scene is different from the Munich scene, and we are from the Düsseldorf scene, from the Rhein / Ruhr scene, which is an industrial area, so our music has more of that edge to it.”

“Our music has been called ‘industrial folk music’,” acknowledges Hütter. “That’s the way we see it. There’s something ethnic to it; it couldn’t have come from anywhere else. The Berlin scene is different from the Munich scene, and we are from the Düsseldorf scene, from the Rhein / Ruhr scene, which is an industrial area, so our music has more of that edge to it.”

Initially, Ralf and Florian gave their musical ideas a firm rhythmic base by adding drummers Andreas Hohman and Klaus Dinger to the Kraftwerk ranks. This line-up, aided by legendary producer Conny Plank, made the first LP, Kraftwerk, on which treated flute and keyboard patterns are joined by electronic oscillations and the kind of industrial noise signalled by the group’s name, which means ‘Powerplant’. Hohman left shortly after, but the remaining trio was soon expanded to a quintet by the addition of bassist Eberhardt Krahnemann and guitarist Michael Rother.

The results weren’t to Hütter’s taste, and after one session he and Krahnemann left the group before Rother and Dinger, sensing a shared psychedelic proto-punk sensibility, themselves split to form the splendid Neu!. Only one (unreleased) session was recorded by the Schneider/Rother/Dinger line-up, though an 11-minute appearance by the trio on the German Beat Club TV show has apparently since been released on laserdisc in Japan. Hütter rejoined Schneider back at Kling Klang Studio, where they made Kraftwerk 2, on which the beats were provided by primitive drum machine and echo units which imposed rhytmic structures on their instruments. Indeed, the track ‘Klingklang’ shares with Sly And The Family Stone’s ‘Family Affair’ the distinction of featuring the first recorded drum machine in pop, both pieces appearing in 1971

A third album — the relatively tranquil Ralf and Florian — followed before, still looking to expand their sound, they brought in drummers Karl Bartos and Wolfgang Flur. The latter, whose band The Spirits Of Sound broke up when Michael Rother had been poached by Kraftwerk, was consequently a little peeved at first when Hütter called to invite him to join, but knew on which side his bread was buttered.

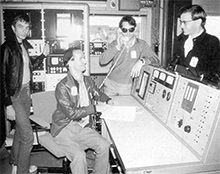

At that time, Kling Klang Studio was far from the technological hub it would become. “The studio was a big room in an old factory building with brick walls,” recalls Flur. “There were big home-made speakers, amplifiers and so on. Florian had his side, with his flutes and one of the very first Arp Odyssey synthesizers, while Ralf’s side had Hammond and Farfisa organs and a MiniMoog synthesizer. But they only had a children’s drumkit, which I didn’t like, so I found a little rhythm machine from an organ. It had knobs and switches, which we could press to play a bass drum, snare drum, cymbal or anything. It was a very elegant way to play, just with fingertips, and the sound was great.”

At that time, Kling Klang Studio was far from the technological hub it would become. “The studio was a big room in an old factory building with brick walls,” recalls Flur. “There were big home-made speakers, amplifiers and so on. Florian had his side, with his flutes and one of the very first Arp Odyssey synthesizers, while Ralf’s side had Hammond and Farfisa organs and a MiniMoog synthesizer. But they only had a children’s drumkit, which I didn’t like, so I found a little rhythm machine from an organ. It had knobs and switches, which we could press to play a bass drum, snare drum, cymbal or anything. It was a very elegant way to play, just with fingertips, and the sound was great.”

It also provided Ralf and Florian with the first of a series of aphorisms with which to describe their work: “Our drummers don’t sweat anymore,” they would say when, out of the blue, their 1974 single ‘Autobahn’ was a huge hit the world over. Blending the hypnotic rhythmic style of classical American minimalist composers such as Steve Reich, Philip Glass and LaMonte Young with the European representative traditition, they had stumbled onto what would be the Great Idea of their career: Romantic Realism. “Walk in the streets and you have a concert, cars playing symphonies,” Hütter would claim. “Even engines are tuned, they play free harmonics. Music is always there — you just have to learn to recognise it.”

For ‘Autobahn’, the group applied impeccable logic to their recording methods, driving around with a microphone outside the car window, taping the automotive ambience, then using the real sounds as templates for their synthetic approximations of car sounds, doppler shifts and the like. But unlike real traffic noise, Kraftwerk’s faked version has a deeply satisfying, amenable sound: realism polished to an attractive, Romantic lustre — what rock critic Lester Bangs in 1975 called their “intricate balm”. “What we are doing is making sound-pictures of real environments, what we call tone-films,” said Schneider, while Hütter was at pains to point out the exactitude of their work: “We strive for clarity, not nebulosity; we are trying to recreate realism, not vague images. In our music we make the machines sing: in ‘Autobahn’, the cars hum a melody, in ‘Trans-Europe Express’ the train sings.”

For ‘Autobahn’, the group applied impeccable logic to their recording methods, driving around with a microphone outside the car window, taping the automotive ambience, then using the real sounds as templates for their synthetic approximations of car sounds, doppler shifts and the like. But unlike real traffic noise, Kraftwerk’s faked version has a deeply satisfying, amenable sound: realism polished to an attractive, Romantic lustre — what rock critic Lester Bangs in 1975 called their “intricate balm”. “What we are doing is making sound-pictures of real environments, what we call tone-films,” said Schneider, while Hütter was at pains to point out the exactitude of their work: “We strive for clarity, not nebulosity; we are trying to recreate realism, not vague images. In our music we make the machines sing: in ‘Autobahn’, the cars hum a melody, in ‘Trans-Europe Express’ the train sings.”

To some, however, Kraftwerk’s realism embodied a cold, impersonal manner: sure, the machines were singing, but where were the feelings? For those brought up on blues-based rock’n’roll, a music that depended upon, and reified, the extravagant expression of emotion, this “mechanic ballet” seemed impersonal and so… Teutonic. Lester Bangs’s Kraftwerk feature in the NME caused a mild furore because of the layout’s crude, parodic use of Nazi imagery, and the headline “The Final Solution”. (In the piece, when Bangs suggests that hypothetical brain implants capable of transferring thoughts instantly into music might be “the final solution to the music problem”, Ralf Hütter actually demurs politely — “No, not the solution. The next step.”)

For their own part, Kraftwerk paid as much meticulous attention to their visuals as to their music, with their designer Emil Schult developing a seamless, impermeable image whose effect was manifold. At the simplest level, the gleaming neatness of their hair and quintessentially manifold suits in the exquisite photographs of the Trans-Europe Express sleeve self-deprecatingly satirised their reputation as unemotional laboratory boffins or tailors’ mannequins, pre-empting the crassest of criticisms; at a deeper level, the photos oozed nostalgia for the lost, pre-war European culture which is one of the album’s more poignant subtexts. As the classically-trained percussionist Karl Bartos told journalist Pascal Bussy, “I remember thinking that with the four of us, Kraftwerk looked a bit like an odd string quartet. Concerning the clothes, it was basically the same: I had to wear a suit to perform classical contemporary things, and I also had to wear a suit with Kraftwerk!”